In the last email, we considered a training strategy for someone interested in using heart rate to direct the intensity of their training effort – the Rookie.

Today, we’re going to focus on the Enthusiast.

Our Enthusiast has been training consistently for some time. They monitor their workouts, food, mood, sleep, and goals in their training journal or smartphone app.

The Enthusiast is active and occasionally participates in a sport or event. Though training and sport is a joy, the Enthusiast has to balance their training with their other responsibilities.

The Enthusiast is looking to maximize the effect of their training for the limited time each day they have for it. They believe incorporating heart rate training zones into their program will improve performance and maximize results.

For the Enthusiast, we will want to run some performance tests. These tests will help pinpoint the three crucial heart rates – aerobic threshold, anaerobic threshold, and max heart rate.

You will want to use a chest strap heart rate sensor for your tests.

Knowing the heart rates associated with the different energy systems (phosphagen, glycolytic, and oxidative) can help guide your training focus.

For a review of the energy systems, go back to the email I wrote about it. Follow the link below.

Energy systems decoded – The key to achieving your fitness goals

Perceived Exertion and the Borg CR-10 Scale

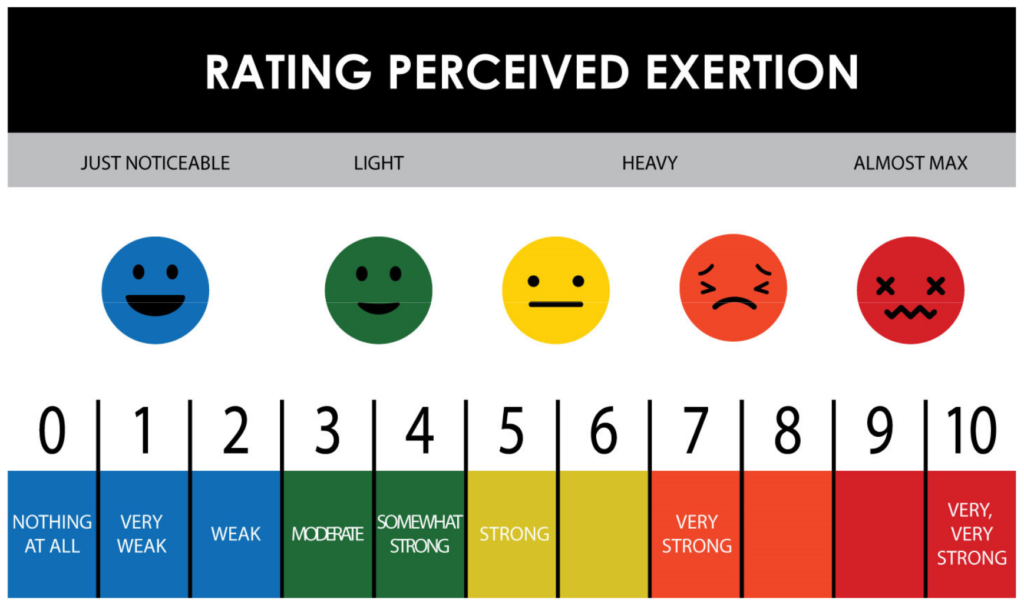

Rates of perceived exertion (RPE) using the Borg CR-10 scale correlate well with one’s aerobic and anaerobic thresholds. Your aerobic threshold has an RPE of 4 on a 1–10 scale. In comparison, your anaerobic threshold is 7. (1)

You can use RPEs to establish the correct intensity throughout your tests. Use the graphic below to serve as a guide.

Finding Your Aerobic Threshold (AeT) – The Talk Test

The talk test is a method used to determine one’s AeT. It involves assessing the ability to speak while exercising.

Below your AeT, breathing is comfortable, and one can hold a conversation easily. However, above the aerobic threshold, there is a noticeable shift in ventilation, making it more difficult (but not impossible) to talk.

For two weeks, test your AeT using the talk test for the first 20–30 minutes of your workout. It’s best to do this on a treadmill or rower. If you do the test outdoors, pick a nice day and a flat course.

Start with an easy 10-minute warm-up. Notice your heart rate. It should be stable to within a couple of beats up or down for a few minutes before moving on. And you want to be clearly below your AeT (RPE 2–3).

When you’re ready to begin the test, pick up the speed so that your heart rate rises 5 beats per minute (bpm) and is steady.

Once your heart rate has been steady for a few minutes, start talking and keep talking for about 30 seconds. If you’re below your AeT, you should be able to speak for 30 seconds without gasping for air.

Repeat the above steps, increasing your heart rate by 5 bpm each stage until talking becomes too challenging to maintain without having to stop to breathe.

When you cannot talk, reduce your effort so your heart rate goes down 5 bpm. If you can go back to talking, hold this pace for 5 minutes. If you’re still able to speak, you’ve found your threshold.

Record the heart rate for your AeT in your training journal. Repeat the test often. Warm-ups are a great time to do this.

Finding Your Anaerobic Threshold (AnT)

The anaerobic threshold goes by many names — lactate threshold, ventilatory anaerobic threshold, the onset of blood lactate accumulation, the onset of plasma lactate accumulation, heart rate deflection point, and maximum lactate steady state.

Whatever you want to call it, knowing the heart rate associated with your AnT will allow you to structure your training deliberately.

Training above your AnT has many of the same benefits as Base Training, but more specifically, it improves your body’s ability to continue to produce energy at higher workloads.

The most straightforward test I know of is a 30-minute time trial developed by Joe Friel. One study compared Friel’s 30-minute time trial to other methods. The study found Friel’s time trial to be the most effective at accurately estimating heart rate at the lactate threshold. (3)

Joe Friel is an endurance sports coach and author of several books, including “The Cyclist’s Training Bible” and “Triathlon Science”. Friel holds a master’s degree in exercise science and is a USA Triathlon and USA Cycling certified elite-level coach. He has coached athletes at various levels, including Olympic athletes and winners of major triathlon events.

30-minute Time Trial (TT) Directions

On the test day, be sure you are well-rested and adequately fueled.

If you’re running, select a relatively flat course. If using a treadmill, set the inclination to 1% grade.

If you’re walking, use a treadmill and work with speed and inclination to find the appropriate effort.

- General warm-up: Take 15 minutes to get warmed up. Your warm-up should include loaded range of motion of all your major joints (e.g., pull-ups, push-ups, squats, lunges, trunk flexion/extension/rotation)

- Test prep: Before the TT, run or walk for 10 minutes. You want to be just below your AeT (RPE 4).

- TT 10/30: For the first 10 minutes of the 30-minute TT, run or walk at an RPE of 7. Take this time to explore the relationship between pace and effort.

- TT 20/30: For the final 20 minutes of the 30-minute TT, begin recording your heart rate. Run or walk for 20 minutes at the strongest pace you can maintain. At the end of 20 minutes, stop the heart rate monitor and record the distance covered and average heart rate.

- Cool-down: Slow down and walk for 5 minutes. Finish with 10 minutes of self-massage and slow stretching.

The goal of the 30-minute time trial is to run as far as you can in 30 minutes.

Though you are going for 30 minutes, you will only record the final 20 minutes of heart rate. The average heart rate over 20 minutes is your estimated lactate threshold.

Once your time trial begins, keep an eye on the time, but do not look at your heart rate or distance. Your focus is on running or walking as far and as fast as possible.

If you can go faster, go faster. If you need to slow down, slow down. Use an RPE of 7 as a guide.

Joe Friel recommends athletes repeat this test every 4–6 weeks. For our Enthusiasts, once or twice a year should suffice.

Your Max Heart Rate

Your max heart rate (MHR) is the maximum beats per minute (BPM) that your heart can beat. Genetics determines your MHR. MHR incrementally declines as you age.

Exercise testing is generally considered safe. However, there have been reports of myocardial infarction and even death, with an estimated occurrence rate of up to 1 per 10,000 tests. (4)

If you have a reason to be concerned about this, talk to your Doctor.

Additionally, if you know your AeT and Ant, you don’t need to know your MHR.

Getting your heart to max out is like getting a personal record in a one-rep max in a big lift (squat, deadlift, press, etc.). This level of demand suggests you’re likely to miss your actual max, especially on the first try. You will need to prepare mentally and physically for the effort.

Modeled on two studies, I’ve laid out a simple protocol described below. (5,6) For this test, you’re going to want someone to make adjustments to the speed of the treadmill while you run.

Max Heart Rate Test Directions

- General warm-up: Take 15 minutes to get warmed up. Your warm-up should include a loaded range of motion of all your major joints (e.g., pull-ups, push-ups, squats, lunges, trunk flexion/extension/rotation)

- Test Prep: Start your heart rate monitor. Set the inclination of the treadmill to 3% grade. Run or walk for 20 minutes below your AeT (RPE 4). It will take a few minutes to find the speed at which you can maintain a steady heart rate.

- First Run: Run or walk for 4 minutes at your AnT (RPE 7). If this is your first time, it will take a minute to find your correct speed. If you’re walking, increase elevation until you’re at the proper effort.

- Recovery: Run or walk for 2 minutes at the speed you used during the On-ramp. You want to be below your AeT. Adjust the speed or inclination of the treadmill as necessary.

- Second Run: Begin this effort at your First Run speed. Every 30 seconds, increase your speed by .5–1 mph (inclination by 1–2% every minute if walking) until you cannot maintain the pace. You want to reach exhaustion in 3–4 minutes.

- Cool-down: Reduce the grade to 0% and walk for 5 minutes. Finish with 10 minutes of self-massage and slow stretching.

Record your max heart rate achieved, treadmill speed, and inclination following your test. These settings will be helpful the next time you conduct the test.

Though the treadmill elicits the highest heart rates, you can perform the MHR test, Talk Test, and 30-minute TT using a rowing machine.

I recommend performing the tests in the order listed. Spend some time getting familiar with your AeT and AnT. Knowing the heart rate associated with these thresholds will help direct your MHR test.

Next email in series

Heart rate training zones – pt 4, three zone model

1. Dantas, José L., et al. “Determination of Blood Lactate Training Zone Boundaries With Rating of Perceived Exertion in Runners.” Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, vol. 29, no. 2, Feb. 2015, pp. 315–20.

2. Alsamir Tibana, Ramires, et al. “Is Perceived Exertion a Useful Indicator of the Metabolic and Cardiovascular Responses to a Metabolic Conditioning Session of Functional Fitness?” Sports, vol. 7, no. 7, July 2019, p. 161.

3. Mcgehee, James C., et al. “A Comparison of Methods For Estimating the Lactate Threshold.” The Journal of Strength & Conditioning Research, vol. 19, no. 3, Aug. 2005, pp. 553–58.

4. Vilcant V, Zeltser R. Treadmill Stress Testing. [Updated 2023 Jun 20]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; January 2023.

5. Ingjer, F. “Factors Influencing Assessment of Maximal Heart Rate.” Scandinavian Journal of Medicine & Science in Sports, vol. 1, no. 3, Sept. 1991, pp. 134–40.

6. Faff, Jerzy, et al. “Maximal Heart Rate in Athletes.” Biology of Sport, vol. 24, no. 2, 2007, pp. 129–42.