In the last email, we introduced our Enthusiast’s three-zone heart rate model. If you missed that one, you can find it linked below.

Heart rate training zones – pt 4, three zone model

Today, we will consider additional heart rate training zones (HRTZ) for Athletes.

Our Athlete regularly tests themselves and their program in competition. For them, event placement and the “personal best” is the goal. Training is the path to their achievement and success in sport.

The Athlete needs to know their HRTZ and how they relate to their sport to optimize their performance.

In today’s email, I must make a couple of distinctions. We will make a distinction between a professional athlete and a recreational athlete.

The pro-athlete competes at the collegiate or professional level. Their coaches and the program will primarily direct their training.

The rec-athlete typically has another job or primary responsibility but takes their training and competition seriously. The rec-athlete is often but not always their own coach. They may have competed at the collegiate or professional level earlier.

Our focus today will be on the rec-athlete.

Though each athlete will have particular requirements to optimize their performance in a given sport, any athlete will benefit from doing four things:

- Maintain a detailed training journal.

- Measure morning resting heart rate and HRV. Use your chest strap monitor and an App that can capture HRV.

- Use a chest strap heart rate monitor and record heart rate data for all conditioning workouts.

- Regularly use field tests to monitor program effectiveness and readiness state.

This email turned out longer than the rest. But to keep this email from turning into a book, I will briefly offer some general heart rate training ideas for three types of athletes: Endurance, Weightlifters, and CrossFit.

Endurance Athletes

General concepts:

- Glycolytic and oxidative energy systems are dominant.

- Approximately 80% of training will be sport-specific and in Zones 1 and 2.

- Cross-training will comprise about 20% of total training, including strength and Zone 4 and 5 efforts.

Building the base (Zone 2)

According to Iñigo San-Millán, the low-hanging fruit that many athletes miss is Zone 1 and 2 work.

Iñigo is a well-known figure in exercise physiology and sports science. Iñigo is a professor at the University of Colorado School of Medicine and the director of performance at the Athletic Club.

Iñigo’s work focuses on physiology, metabolism, and mitochondrial function in health and disease. San-Millán has researched the impact of endurance exercise on boosting mitochondria and the role of exercise in reversing Type 2 diabetes.

In an article for the Training Peaks website, Iñigo writes, “Many novice or young athletes barely train or are prescribed Zone 2 training and therefore don’t develop a good “base,” thinking that the only way to get faster is by always training fast. By doing this, they won’t improve nearly as much as if they trained Zone 2 in large amounts.” (1)

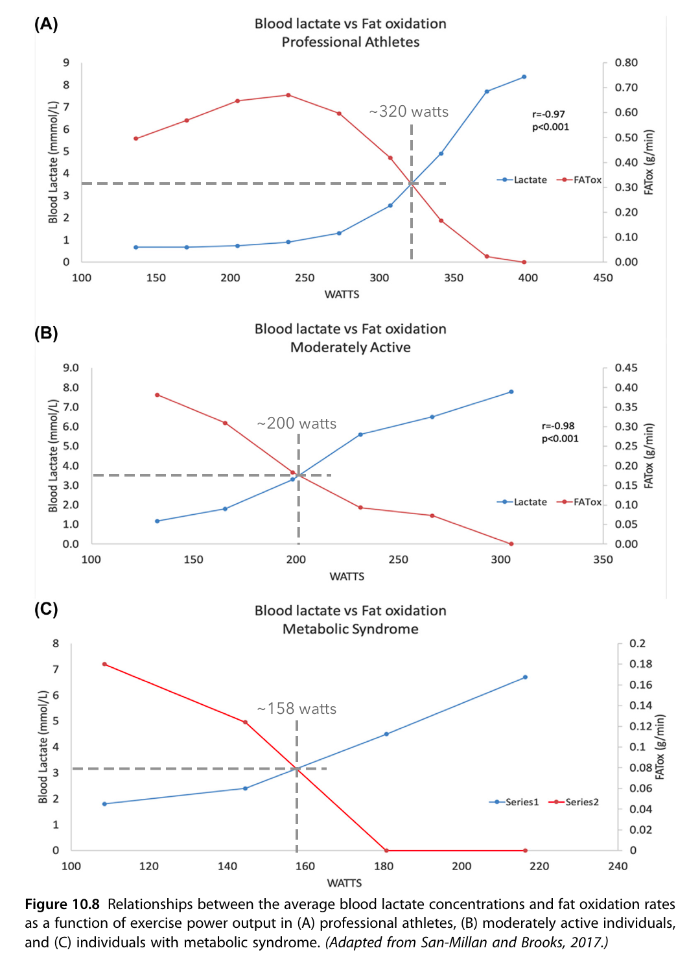

The graph below is from research done in Iñigo’s lab. I added the dotted grey lines to highlight the “crossover point” at which fat oxidation and blood lactate cross as exercise intensity increases. (2)

One could read the graph as representing a gradient of health that goes from unhealthy to the most fit metabolically.

Moderate activity will keep you out of the pit of metabolic syndrome. But to achieve an athlete’s metabolic health, you will need to spend more time in Zone 2.

“The ideal training plan should include 3-4 days a week of Zone 2 training in the first 2-3 months of pre-season training, followed by 2-3 days a week as the season gets closer and two days of maintenance once the season is full-blown.” (1)

The duration of a training session depends on the individual’s fitness level and goals. However, these sessions are typically 60–120 minutes.

If you still need to incorporate deliberate Zone 2 training days in your program, pick one or two of your long workouts and maintain whatever pace you need to stay below your aerobic threshold (AeT).

Many runners are surprised to find they need to walk when starting to remain under their AeT.

Polarized training

Forty-eight experienced runners, cyclists, triathletes, and cross-country skiers participated in a nine-week study. The study compared four training methods for improving VO2, time to exhaustion during a ramp protocol, and peak velocity and power. (2)

The four training methods were high-volume training, lactate threshold training, HIIT, and a combination of the three referred to as “polarized training.” Body fat was also assessed.

Of the four methods, polarized training and HIIT resulted in the most significant improvements in VO2 and time to exhaustion. HIIT produced the greatest amount of fat loss (~3%).

Lactate threshold and high-volume training alone did not lead to further improvements in highly trained, experienced athletes.

The polarized training program consisted of three blocks, each lasting three weeks. In the first two weeks of each block, participants engaged in high-intensity and high-volume training involving six sessions.

These six sessions were:

- Two 60-minute HIIT sessions.

- Two long-duration sessions of 150–240 minutes.

- Two 90-minute low-intensity sessions.

All HIIT sessions included a 20-minute warm-up at 75% MHR (Zone 2). The warm-up was followed by four intervals of 4 minutes at 90–95% MHR (Zone 5), with 3 minutes of active recoveries at 75% MHR. And ending with a 15-minute cool-down at 75% MHR.

Each long-duration session contained 6–8 maximal 5-second sprints, with at least a 20-minute interval between.

The 90-minute low-intensity sessions were intense, resulting in blood lactate of less than 2 mmol/L (Zone 2).

The third week of each block was designated as a recovery week, during which participants participated in one 60-minute HIIT session, one long-duration session lasting 120–180 minutes, and one 90-minute low-intensity session.

Powerlifters, Weightlifters, and Strongman

General concepts:

- Phosphagen energy system dominant.

- Approximately 15% of training will be sport-specific heavy lifting.

- Approximately 85% will be accessory work, GPP, and conditioning (Zones 2 and 4).

Conditioning plays a supporting role in performance, recovery, and longevity.

If you visit the forums of powerlifters, a typical response to “What do you do for cardio?” is “More than six reps.”

Though this is said in jest, strength athletes today understand the importance of doing some conditioning. But what they do and how they do it is pretty varied.

Some do high-intensity interval training (HIIT). Some ruck and do farmer carries, sled drags, and walk wearing ankle weights and carrying dumbbells. Some run or cycle.

General physical preparedness (GPP)

Louie Simmons (Oct 1947 – Mar 2022) was a renowned strength coach and powerlifter who founded Westside Barbell, a gym and strength training education company.

Westside Barbell has produced many world-class powerlifters, coaches, and athletes who have set numerous world records and won multiple national and international championships.

Louie used to say that “the higher you want to go, the wider your base needs to be.” He likened it to a pyramid. The taller the pyramid, the larger the base. (3)

Louie had his athletes regularly do sled drags, wheelbarrow walks, farmer and yoke carries. He would load athletes with weight vests and chains, and they would walk.

Louie firmly believed in the power of general physical preparedness (GPP). For Louie, GPP meant being able to enter a meet or other weightlifting challenge with little to no prep time. (4)

Zone 2 for strength

According to Ben Pollack, low-intensity, steady-state cardio (Zone 2) is a much better option than high-intensity training for powerlifters. (5)

Ben Pollack is a professional powerlifter and holds the all-time world record for a raw total of 2039 lbs in the 198 lb class. Ben earned his Ph.D. in the history of strength from the University of Texas in 2018.

Ben suggests starting with a 15-20 minute cardio session on one of your non-training days. If all goes well, you can add more sessions. Ben believes that anything over 30 minutes will eat into one’s recovery.

HIIT for strength

An eight-week study of experienced powerlifters and strongman athletes found that 20 minutes of high-intensity interval training (HIIT) twice a week improved aerobic capacity without impacting strength. (6)

Participants were divided into two groups – an aerobic mode (AM) and a strength mode (SM). The intensity was controlled using the percent of max heart rate (MHR) and rates of perceived exertion (RPE).

The AM group was instructed to maintain 85% MHR and RPE of 8 (Zone 4) during the work portion and 60% MHR and RPE of 5 (Zone 2) during the recovery. At the same time, the SM group used RPE 8–9 for their work portion and passive recovery.

Running the experiment

A strength athlete would benefit from incorporating HRTZ into their conditioning for the following reasons.

For any person, strength athlete or not, conditioning should improve VO2. For VO2 to improve, there must be an increase in mitochondrial density and efficiency. (1)

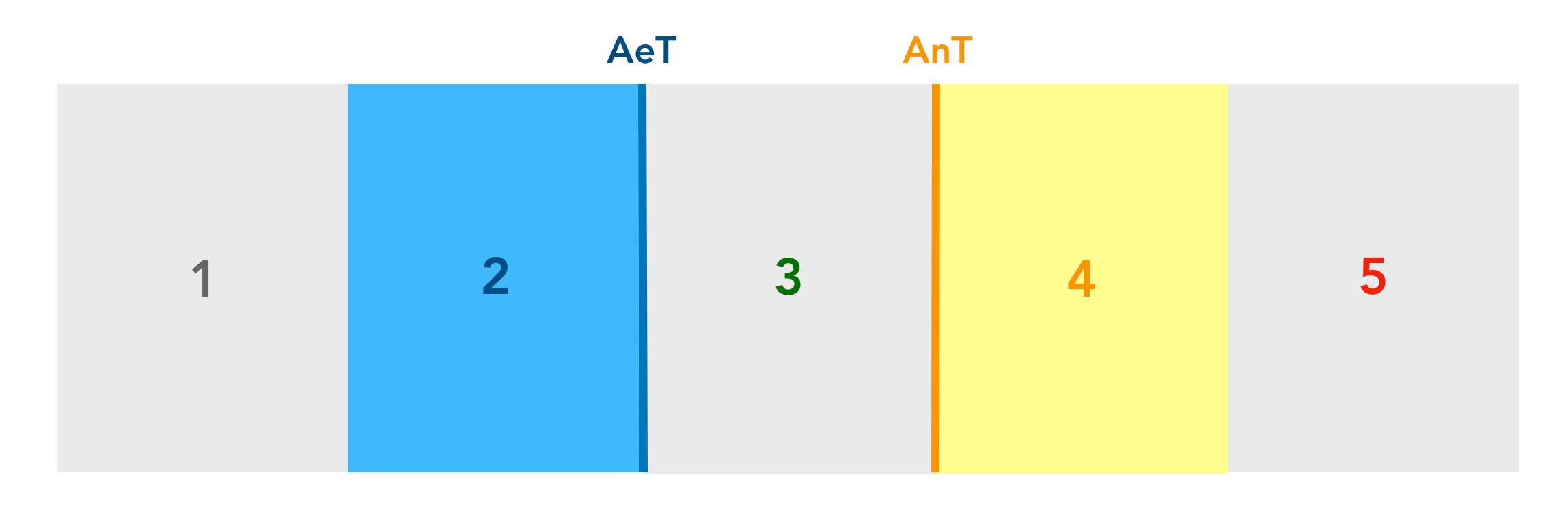

Training near but not above your aerobic threshold (AeT) and above your anaerobic threshold (AnT) significantly impacts VO2. (6)

Using a 5-zone heart rate training model, one would focus their conditioning on Zones 2 and 4.

Each athlete will have to experiment to find out the optimal amount. To start, I recommend strength athletes incorporate HRTZ into the conditioning they’re currently doing.

If an athlete is doing two 20-minute conditioning sessions a week, then make one of them 20 minutes of Zone 2 and one of them 20 minutes of Zone 4. Do this for eight weeks and track your results.

CrossFit Athletes

General concepts:

- All energy systems are developed.

- Optimizing GPP is the primary goal.

- 50% of training will be dedicated to strength & conditioning.

- 50% of training will be dedicated to weightlifting & gymnastics.

Surveying the elite

Seventy-two CrossFit athletes (39 females, 33 males) who competed at the Regionals level or higher in the 2018 CrossFit Games season completed a self-reported 5-page online survey. (7)

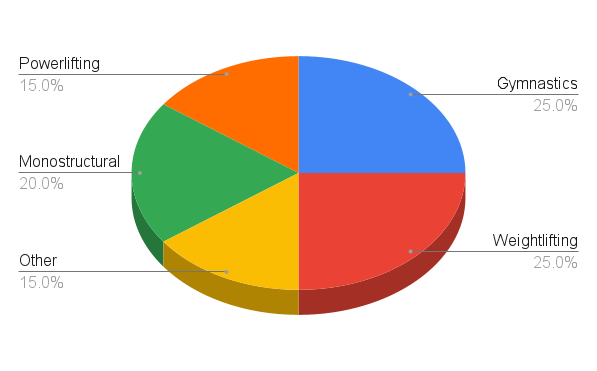

According to the survey, elite CrossFit (CF) athletes train approximately 90-120 minutes a day, 5-6 days a week. The chart below shows the average training time by modality as a percent of total training.

Powerlifting would be deadlifts, squats, bench presses, and other heavy lifting, including stones, sandbags, kegs, etc.

Monostructural would be long runs, rides, rows, etc.

Other is likely metcon (metabolic conditioning) in the form of high-intensity circuits or intervals.

Gymnastics includes elements from the sport of gymnastics and almost anything bodyweight-oriented. Gymnastics include handstand push-ups and walking, ring and bar muscle-ups, legless rope climbs, and peg boards.

Weightlifting consists of the barbell clean & jerk, the snatch lifts, and various skill transfer exercises.

Intelligent intensity

A CF athlete would benefit from incorporating HRTZ into their conditioning programming by ensuring that on monostructural days, they’re including 45–90 minutes of Zone 2.

And on metcon days, they’re structuring their workout intelligently so that their heart rate is driven into Zones 4 and 5, and doesn’t get stuck in Zone 3.

Regularly field test using CrossFit Games and Open events.

Next email in series

Heart rate training zones – pt 6, Professionals

(1) Iñigo San-Millán. “Zone 2 Training: Build Your Aerobic Capacity.” Training Peaks, 2 April 2014. https://www.trainingpeaks.com/blog/zone-2-training-for-endurance-athletes/

(2) San-Millán, Iñigo. “Assessing Metabolic Flexibility and Mitochondrial Bioenergetics.” Clinical Bioenergetics, Elsevier, 2021, pp. 245–68.

(3) Stöggl, Thomas, and Billy Sperlich. “Polarized Training Has Greater Impact on Key Endurance Variables than Threshold, High Intensity, or High Volume Training.” Frontiers in Physiology, vol. 5, 2014.

(4) Westside Barbell. (4 December 2020). Louie’s Lesson: The Importance of General Physical Preparedness [GPP]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=rW3yS86vYL8

(5) Simmons, Louie. Westside barbell book of methods. Westside Barbell, 2007, p.159.

(6) Ben Pollack, Ph.D. “Cardio and Powerlifting: The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly.” BarBend, 16 Aug 2023, barbend.com/cardio-powerlifting/.

(7) Androulakis-Korakakis, Patroklos, et al. “Effects of Exercise Modality During Additional’ High-Intensity Interval Training’ on Aerobic Fitness and Strength in Powerlifting and Strongman Athletes.” Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, vol. 32, no. 2, Feb. 2018, pp. 450–57.

(8) Pritchard, Hayden J., et al. “Tapering Practices of Elite CrossFit Athletes.” International Journal of Sports Science & Coaching, vol. 15, no. 5–6, Dec. 2020, pp. 753–61.